Appendix

Adult Books and Stage Play

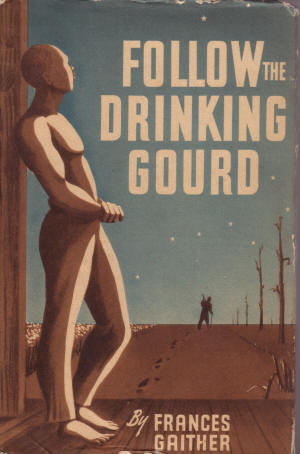

Frances Gaither, Follow the Drinking Gourd

Frances Gaither, Follow the Drinking Gourd, Macmillan: New

York, 1940.

Synopsis

SPOILER ALERT: Many "plot spoilers" in this section. Stop now if you

would rather not read them!

PART I. John Austen is the proprietor of Hickory Vale in Georgia. His

land failing, Austen purchases virgin property in Alabama. The overseer,

Newsom, brings Austen's slaves and livestock overland to Hurricane.

Austen is portrayed as a benevolent owner, "Don't forget we have to

raise plenty of corn and pork, too, Newsom."..."These boys are like

members of my family."

Soon after Austen returns to Georgia the first of Hurricane's many

disasters strikes – a week of rain that beats the corn down flat and

washes up the cotton. The crops recover somewhat, but set a pattern by

yielding less than is necessary to meet the mortgage. Newsom takes the

young slave woman Juno as his servant.

PART II. John Austen is dead. We learn in a flashback that Juno was

found to be pregnant and later dies while giving birth to Newsom's premature

child. After Newsom is fired, the new overseer drives the slaves hard;

food crops are neglected in favor of the cotton cash crop. We meet the

young slave Poldo – very smart and excellent with figures.

For the first time, slaves are whipped for not working hard enough. A

huge storm lays waste the plantation. After the storm's destruction, the

overseer is a changed man, "The rain-wet bales, which might yet

have fetched a fair price if promptly opened and dried, were left to

mildew and rot." Food is very short. The slaves learn that their

plantation is sunk deeply in debt and they are at risk of being sold.

John Austen's son Robert takes up residence, "Standing among his people

he was smiling, almost gay." The local Squire attempts to compliments

him, "It certainly warms my heart to see how you handle them, son. Your

manner with them is perfect; easy as an old glove." The comments sit

badly with Robert, who had thought prior to his arrival to emancipate

his slaves.

After a confrontation, the overseer leaves. The slaves work devoutly

for Robert and broach the idea of carrying on without an overseer. The

creditors don't agree. Robert weeps when they later seize a slave couple

and three of their children.

Cholera strikes neighboring plantations. The slaves start dying.

Robert ministers to Poldo, then takes ill himself and dies suddenly.

PART III. Hurricane is in disarray. Having passed out of the family,

it is now run for the benefit of the bank. A new overseer rejuvenates

the plantation. Poldo is his right-hand man, but his father warns

him on his death bed to be humble, that his status could change in an

instant.

Peg Leg Joe, a journeyman carpenter, arrives to help build a new

house for the overseer and his fiancée. Joe confides to Poldo that he is

an Underground Railroad agent. Joe transmits detailed directions and

promises to leave his "mark" along the route. Realizing he has given Joe

his best hands to help build the house, Poldo fears for Hurricane. He

overhears the hands singing the

Drinking Gourd song, at first making out only the melody but not

the words.

Poldo's wife Mary (Newsom) is carrying on with a free black. She is

pregnant, and it's not certain who the father might be. Mary's paramour

buys her out of slavery and spirits her away on his ship. Five

runaways escape en masse from Hurricane. Poldo's relationship with the

overseer is at risk, and the overseer's wife accuses Poldo of knowing

more than he admits.

Poldo prepares to leave, as if in a dream. En route, as Poldo stared

at Joe's "painted sign, he began to hear, word by word, names of rivers,

names of places, names of stars...The Tombigbee is a plain road all the

way to north Alabama. From there it's only a stone's throw to the

Tennessee. And the Tennessee's another clear road to follow." He also

has Joe's directions on how to link up with the Underground Railroad. At

one ford, a raft awaits him, had Joe left it? "A word shaped itself in

Poldo's mind and found its way to his tongue. 'Free.'"

Use of the

Drinking Gourd song

The book quotes the first verse of the Parks lyrics on the title page,

rendered in standard English. An Author's Note precedes Part I:

All of the characters in this story are fictional except Peg-leg

Joe, a real person associated in Southern legend with the Drinking

Gourd song and with that part of Alabama where it was once

current.

Various elements from the song and the Parks account describing it

are woven into the novel. For example, looming overhead "...swung the

Great Dipper – the Drinking Gourd, as the Children and Negroes called

it." Both master and slave know that the first quail calling signifies

the spring, here tied to plowing time.

Peg Leg Joe is a journeyman carpenter. He transmits

detailed directions and promises to leave his "mark" along the route.

He also tells prospective escapees how to link up with the Underground Railroad.

A conspiring group of slaves "had a song, made up among themselves

or taught to them by the visiting carpenter, which...they took particular pains to keep secret."

(p. 228.) Slaves describe the Drinking Gourd as "a bad-luck song do

white folks hear it." (p. 233) This echoes the Parks account

describing the first time he collected the song. (Details

here.)

Other Notes

Frances Gaither, (1899-1955) was born in Somerville, Tennessee. One

of her grandfathers hailed from Maine; the other owned slaves on a

plantation in Tennessee. "Gaither attributed her deep concern with the

plight of Negroes, at least in part, to this mixture of 'raw Yankee and

slaveholding Southern.'" (Ronald L. Davis in Lives of Mississippi

Authors, 1817-1967, pp. 186-187) Several of her

novels dealt with the South in a manner that struck reviewers of the

time as refreshing. In fact, it's clear that in some quarters this book

was seen as the antithesis to Margaret Mitchell's Gone With the Wind,

first published in 1936 and brought to the screen in 1939. "Improbable

as it seems, a novel has been written about the pre-Civil War South

without crinolines or mammies." (see Reviews, below). Also noticeably

absent were "juleps, white columns, coquettes in frilly dresses and

contented darkies singing in the cotton fields." (Davis, ibid.)

The novel received three laudatory review in the New York Times, and

four other mentions. This level of coverage was doubtless due to the

quality of the writing, to its positioning with respect to Gone With

the Wind, and perhaps in some small measure to husband Rice

Gaither's staff position at the Sunday New York Times!

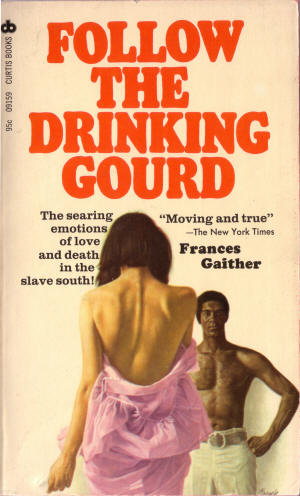

The

book was re-issued in paperback in 1968 with a cover that promised "The

searing emotions of love and death in the slave south". The lurid

illustration stood in marked contrast to the reviewer's blurb, "Moving

and true". (For the record, there are no black man/white woman

relationships in the novel.) The

book was re-issued in paperback in 1968 with a cover that promised "The

searing emotions of love and death in the slave south". The lurid

illustration stood in marked contrast to the reviewer's blurb, "Moving

and true". (For the record, there are no black man/white woman

relationships in the novel.)

Contemporary reviewers noted, "This plantation...is

none we have seen before in fiction." That's certainly true, and

the writing is excellent. Still, today the book does not seem as

revelatory as it must have to its 1940s readers. Nowadays the owners

appear idealized and paternalistic ("These boys are like members of my

family.") and the slaves unduly subservient ("They're the most willing,

obedient set I ever saw when they're handled right [page 89.])

Reviews

"(H)er trilogy (Follow the Drinking Gourd, The Red Cock Crow, Double

Muscadine) now stands alone for its honesty, its reality and the

maturity with which the most delicate phases of the master-and-slave

relationship have been explored." "Mrs. Gaither's South is accurately

and sharply presented. She has a miraculous ear for shadings of speech.

The customs, tensions, and especially the hard lot of women, are all

presented with the care and understanding that give the writing a

firmness of texture rarely found in contemporary fiction."

Herschel

Brickell, "Caste and Class in the Old South", New York Times, March 6,

1949, p. BR5.

"Improbable as it seems, a novel has been written about the pre-Civil

War South without crinolines or mammies.

Mrs. Gaither tells this story straightforwardly and well, with an

unusual gift for creating character and with detached appraisal of the

interdependent difficulties of master, overseer and slave. The book

deserves a place among the serious fictional studies of ante-bellum

economic and social problems.

Mrs. Gaither permits herself one character with a historical basis,

Peg-Leg Joe, 'a real person associated in Southern legend with the

Drinking Gourd Song and with that part of Alabama where it was once

current.'"

Thomas C. Linn, "Books of the Times", March 12, 1940, p. 29

"This plantation...is none we have seen before in fiction. For the

absentee owners it is merely an investment, and not very profitable at

that. For the slaves who live and work, quarrel and make love, marry and

die on Hurricane, it is a self-contained world.

Written with beautiful simplicity and economy, too mellow for

tragedy, 'Follow the Drinking Gourd' nevertheless seems just and

compassionate, moving and true."

Margaret Wallace, "On an Alabama Cotton Plantation", New York Times,

March 17, 1940, p. 92.

The other four mentions in the New York Times:

"Notes on Books and Authors, Forthcoming Books", February 11, 1940, p. 98

"Books to Be Published During the Spring Months", March 10, 1940 p. 94

"Latest Books Received", March 17, 1940, p. 103

"A beautifully written novel of pre-Civil War days in Georgia and

Alabama. Presents the economic wastefulness of slavery and the

social effect of such an institution on all concerned."

Otis W. Coan and Richard G. Lillard, America in Fiction, 4th

edition, 1956

Stanford University Press, p. 47

Awards

Honorable mention, Best Book by a Southern Author, Southern Women's

National Democratic Organization, January 26, 1941, p. 30.

Lorraine Hansberry,

The Drinking Gourd

(Stage Play)

The Drinking Gourd The Drinking Gourd

Voices of Man Literature Series

Vincent L. Medeiros, editor

Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1969

Les blancs: the collected last plays of Lorraine Hansberry.

New York: Random House, 1972

New York: Vintage Books, 1973, 1983, 1994

Black theater, U.S.A.: forty-five plays by Black Americans,

1847-1974. Part 6-12

New York: Free Press, 1974

Readings from The journey (Audio recording; includes two

scenes from The Drinking Gourd)

Scholastic Records, 1971

Synopsis

SPOILER ALERT: Many "plot spoilers" in this section. Stop now if you

would rather not read them!

ACT I opens with an establishing scene: dinner in the slave quarters.

We meet the old servant Rissa and Sarah, her son Hannibal's love

interest. A scene in the moonlit woods follows between Sarah and

Hannibal. It introduces the Drinking Gourd (Big Dipper) star formation,

and the Drinking Gourd song.

The proprietor of the plantation, Hiram Sweet, and his son Everett

meet with their friend Dr. Bullett. Hiram is in bad

health, and Everett chafes at father's continued oversight. Growing cotton has

worn out the land, and the two argue about whether nine and one-half hours

work per day is enough for the

help. The Sweet plantation is "A resort for slaves", according

to Everett, while his father takes a decidedly more paternalistic

position. Doctor Bullett urges that Hiram give up all work in the

fields, for the sake of his health. Hiram

muses about whether owning slaves is a sin.

Rissa has heard the whole exchange from the kitchen. She has irked Hiram, on the

doctor's orders, by withholding salt from his food. Hiram recaps

the humble origins of the farm (Rissa was one of the first slaves) and

reiterates his promise to make Hannibal a house servant. The scene

is one of genial domesticity. The act closes with Hiram thundering about

his position, "...I am master of this plantation and every soul on it."

ACT II. Hiram's wife Maria tells her son Everett that he must

run the plantation. His take-over must be engineered subtly, leaving his

father to believe that he is still in charge.

We meet Zeb, a dirt-poor white, as he is being counseled by a Preacher.

The Preacher opines, "Seems to me three things the South sends

out more than anything else. A steady stream of cotton, runaway

slaves and poor white folks. I guess the last two is pretty much lookin'

for the same thing and they both runnin' from the first." He cautions Zeb

about driving slaves for the likes of the Sweet family, "Them people hate our kind." We meet Zeb, a dirt-poor white, as he is being counseled by a Preacher.

The Preacher opines, "Seems to me three things the South sends

out more than anything else. A steady stream of cotton, runaway

slaves and poor white folks. I guess the last two is pretty much lookin'

for the same thing and they both runnin' from the first." He cautions Zeb

about driving slaves for the likes of the Sweet family, "Them people hate our kind."

The slaves sing a play song that includes lyrics about poisoning the masters.

The driver Coffin, an unpleasant toady, interrupts the scene. Rissa

relates to Hannibal the offer of a house servant position. He is not

interested, wanting only to escape. He demonstrates that he can read, and

Rissa is truly terrified –

slaves learned to read and write at great peril.

As the new overseer, Zeb lays down the law to the slaves, then whips

Hannibal in the face. Coffin later reveals that Hannibal has slipped

away to be with Everett's younger brother, Tommy. Tipped off by Coffin,

Everett and Zeb surprise them. Hannibal is teaching Tommy the banjo and

Tommy is teaching Hannibal to read and write. Hannibal has written a

composition about the Drinking Gourd. In a fury, Everett orders Zeb to blind Hannibal.

(See

here for comments.)

ACT III. An enraged Hiram has learned about the awful deed. He dresses down his son and orders Zeb off the

plantation. Bullett arrives with news of the barrage at Fort Sumter and

the start of the Civil War. Hiram offers a toast to the end of the Southern

way of life. He visits Rissa in her quarters as she tends to Hannibal.

He says plaintively that he had

nothing to do with the blinding (in contrast to his speech at the end of Act I.) She spits back, "Why? Ain't you Marster?"

and turns away from him. He leaves the cabin and collapses

outside, within earshot, crying out for help. Rissa ignores him.

In the final scenes, Everett appears dressed as a Confederate Officer, while

Maria is in mourning clothes. Zeb will run the plantation in

Everett's absence. Wordlessly, Rissa takes Hiram's gun and gives it to

Sarah, who prepares to lead Hannibal and his nephew Isaiah in flight. Follow

the Drinking Gourd is

sung as the slaves flee. The final thoughts of the play belong to a

soldier, intoning that he must fight to hold the Union together. Slavery has already cost the nation "too much of our

soul."

Use of the

Drinking Gourd song

The Drinking Gourd song is introduced early in the first act.

The young slave Hannibal sings the chorus to his sweetheart Sarah in

moonlit woods. The play uses the Weavers' version of the song (including the

"Follow–follow–follow" improvisation added by Ronnie Gilbert.)

The Drinking Gourd is the subject of a composition written by

Hannibal at the end of Act II. The song is also sung near the end of the

play when Hannibal, Sarah and Hannibal's nephew escape the plantation.

Other Notes

Lorraine Hansberry was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1930. Her family settled in a white area when

she was eight, and were

received hostilely by much of the neighborhood. Her parents took a

housing discrimination case to the US Supreme Court. The deeply felt family

lore resulting from that experience provided some of the background for

A Raisin in the

Sun. Opening in 1959, it won the New York Drama Critics' Circle

Award for best play of the year.

Hansberry married Robert

Nemiroff in 1953. They separated in 1957 and divorced in 1964.

Tragically, she died from cancer in New York City in 1965.

Well-known producer/director Dore Schary planned a series of five

ninety-minute television dramas on the NBC network marking the

centennial of the Civil War. He commissioned the lead-off drama from

Hansberry in 1959, telling the playwright that her portrait of

slavery could be "As frank as it needs to be."

Schary recounts how he told network executives that he had engaged

the winner of the Drama Critics' Circle Award to write a screenplay

addressing slavery. One executive asked, "What's her point of view about

it–slavery?" Schary thought he was kidding and answered, deadpan, "She's

against it." Nobody laughed, and Schary later wrote, "...from that moment I

knew we were dead."

Hansberry steeped herself in research and submitted the Drinking Gourd

teleplay in 1960. The script included the song and scenes based on

it, while dealing with the corrosive effects of slavery. Her viewpoint

was clear, "...it is difficult for the American mind to adjust to the

realization that the Rhetts and Scarletts were as much monsters as the

keepers of Buchenwald–they just dressed more attractively and their

accents are softer."

Even though NBC programming vice president David Levy termed it a

superb script, it never aired. Nemiroff thought the script was doomed

not because of its frankness but rather its fairness to the white

characters. He

also suggested that the Rissa's character violated a cherished American

myth: the Black Mammy figure. (See Les Blancs: The Collected Last

Plays, pp. 152-155.)

I find Nemiroff's arguments unconvincing. In 1965, he tried again to

get the show aired. An executive producer of the Hallmark Playhouse

wrote The Drinking Gourd was "a beautiful

script...but frankly...not the sort of thing the sponsor is looking for.

Hallmark is a family show and–well, you know..."

I think the Hallmark Playhouse response is closer to the truth than

any concerns about the play's evenhandedness or Rissa. Blinding a character is a

very powerful dramatic device (see also King Lear and Oedipus!), but extremely

rough going for a prime-time television show. Moreover, while Hansberry

was of course free to follow her muse, blinding

slaves as a punishment for anything, including literacy, was extremely uncommon. (See

here for the details.)

I also thought the play was peopled with stock types. Everett was the

cocksure Southern youth, "...we can have 600,000 men in the field

without even feeling it. The whole thing wouldn't have to last more than

six months." Hiram was the world-weary, sage father, "A way of life is

over. The end is here and we might as well drink to what it was." Maria

was the iron-willed plantation mistress, admonishing her son, "...I have

clearly asked you to be a very strong man. Which is the only kind I have

ever been able to truly love." Zeb was the trashy white overseer,

Hannibal was the headstrong young slave, Coffin was the elderly, toady

servant, "I tries to be a good driver for Marster and (Hannibal's) the

kind what makes it hard for me." Only Rissa present a unique, fully-rounded character.

(And possibly the Preacher, in a much smaller role.) Of course, we are

now nearly 50 years on. Perhaps the characters would have seemed fresher

to the audience of its day.

The network

shelved both the teleplay and the series. In 1967, on the second

anniversary of Hansberry's death, WBAI in New York City broadcast a

two-part program, Lorraine Hansberry in Her Own Words. The show

included two scenes from The Drinking Gourd, and one was later

also used in To Be Young, Gifted and Black (see below.)

According to A History of African American Theatre, the script

was staged in 1974 at the Harlem Community Center for the Arts, with

several subsequent college and community productions. The play was more

recently adapted and staged by Tisch Jones at the University of Northern

Iowa in 1995. According to A History of African American Theatre, the script

was staged in 1974 at the Harlem Community Center for the Arts, with

several subsequent college and community productions. The play was more

recently adapted and staged by Tisch Jones at the University of Northern

Iowa in 1995.

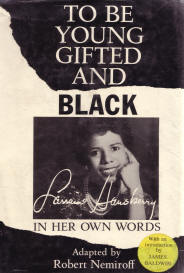

Use of the Play in To Be Young, Gifted and

Black

Hansberry's

To Be Young, Gifted and Black, adapted by Nemiroff from her

writings, was produced Off-Broadway in 1969. It also appeared in book

form the next year. The Drinking Gourd contributes a short

soliloquy by Zeb, about driving slaves for the Sweets, "and this time

next year, Zeb Dudley aims to own himself some slaves and be a

man–you hear!" The moonlit scene between Hannibal and Sarah introducing

the Drinking Gourd (Big Dipper) star formation, and the Drinking

Gourd song appears. There is a sardonic discussion of the play's

fate at a symposium with James Baldwin, Langston Hughes and others,

followed directly by the scene of Tommy Sweet teaching Hannibal to read

and write and Hannibal's blinding at the hands of Zeb Dudley.

Lee Hays, Bend to the Dying Lad (Unpublished)

Bend to the Dying Lad, A Story About Walt Whitman. Lee Hays, 1950. An

unpublished novella based on Follow the Drinking Gourd.

Synopsis

"In the novella, Hays depicts Walt Whitman in the poet's days as a

hospital attendant nursing wounded soldiers from the Civil War. The tune

to 'Follow the Risen Lord,' appears in the novella as one which was sung

separately by two estranged brothers raised on the same Southern

plantation who left to fight on different sides of the war. Both wounded

and being treated in the same hospital (but unknown to one another, at

the time), they sing the song to Lee Hays' fictionalized Walt Whitman,

who is able to reunite the two before they die." (Sing Out,

Warning! Sing Out, Love: The Writings of Lee Hays, Robert S.

Koppelman, University of Massachusetts Press, 2004)

(1)

|